|

|

|

Home Poets Novelists Critics Lidia Vianu Desperado Links Contact

JULIAN BARNES

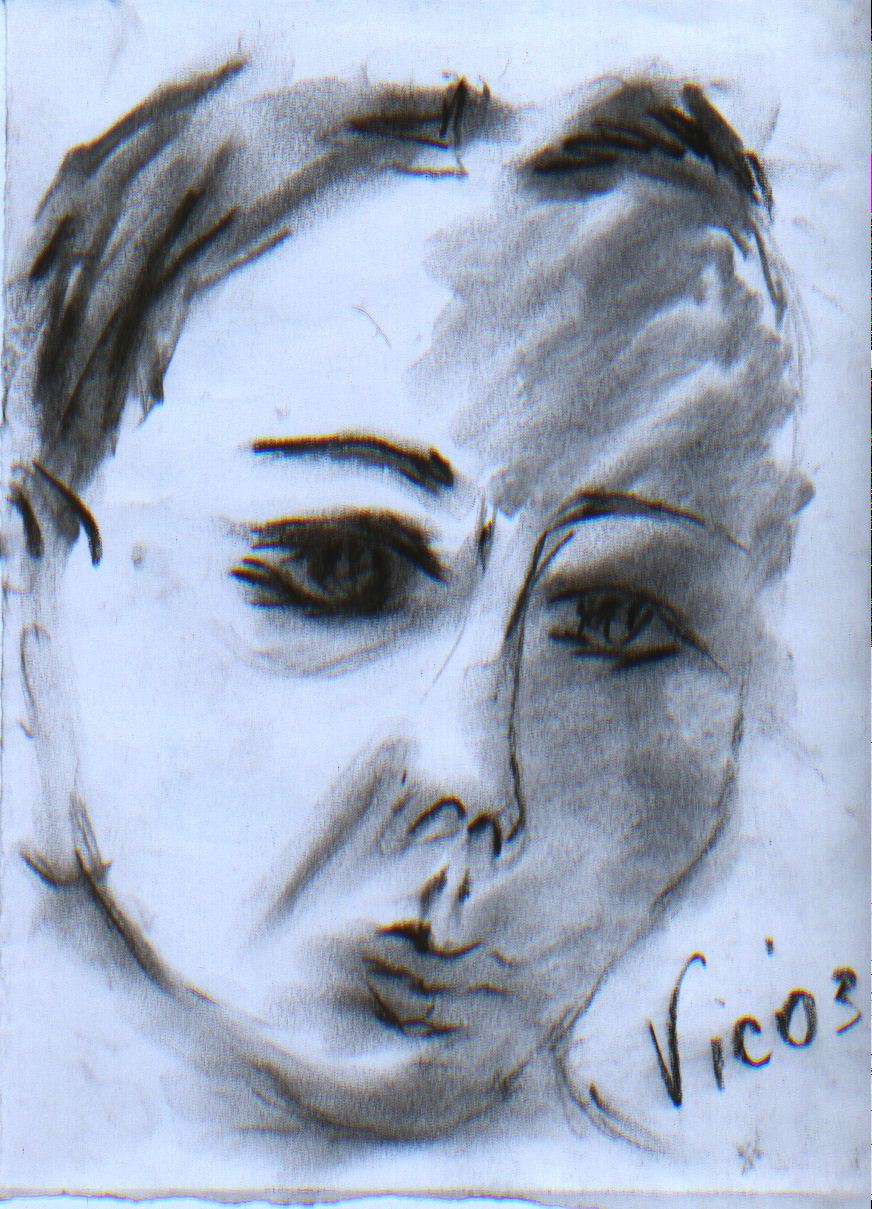

Portratit by VIC (Cristina Ioana Vianu)

Essays on Julian Barnes in

British Literary Desperadoes at the Turn of the Millennium, ALL Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999

The Desperado Age: British Literature at the Start of the Third Millennium, Bucharest University Press, 2004

Giving up criticism is much easier than giving up alcohol or tobacco

Interview with JULIAN BARNES (born 1946), British novelist

Published in LIDIA VIANU, Desperado Essay-Interviews, Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti, 2006

LIDIA VIANU: You belong to a generation of writers who will do anything in their power, form and content (technical and emotional experiment at all costs) to shock, confuse, render the reader helpless. These I have called Desperadoes. Do you feel you relate to the description of the group and to the label?

JULIAN BARNES: Well, I’m rather surprised to be called a Desperado. I rather like the description (who wouldn’t?) but you make us (if there is an ‘us’, which I’m sceptical about) sound like a gang led by Clint Eastwood. But who is Clint, and are we a gang? I think we are a very disparate number of rather quiet writers who write rather differently from one another. I certainly think, for my part, that my aim is NOT to do anything in my power to shock, let alone render the reader helpless. I have a very close and affectionate relationship with my putative reader. At times, of course, I like to play with what I suspect s/he knows or expects; I like to render reality in all its confusing complexity; but I in no way think of my readers as either antagonists or victims. That’s too easy. My reader sits not opposite me, in any case, but beside me, gazing out at the world in a parallel direction. I merely discuss with my friend the reader what I see and think.

LV. You are not part of a trend, though. You are your own trend. How would you describe the ‘Julian Barnes movement’ ? Daring, inquiring, insinuating, starving for the reader’s affection? Or indifferent, independent, haughtily ironical and cold (which it is not, though)?

JB. Well, I never think of myself as a one-man movement, or a writer with particular characteristics. I see things from much closer to the ground. I work at each book as it comes along, and forget the previous ones when I do so. My books are often very different from one another, demanding different technical solutions to different formal and thematic questions. From your galaxy of adjectives, I recognize ‘ironic’ (how could I not?). All I’d say is that the common mistake is that irony precludes sympathy. It doesn’t: see Flaubert.

LV. The emotional life of your characters is your battlefield. You want to protect it (keep it a mystery) but you tear it to pieces (see Talking It Over). The result is what I have called The Down Syndrome of Emotional Fiction: a contradiction which is so stimulating that re-reading becomes a must. Not to study technicalities, but to explore the author’s tricky sensibility. How much of yourself do you invest in these characters? Any autobiographical reference? Where?

JB. Well, isn’t everyone’s life an emotional battlefield? And a novel about characters

with no emotional ups and downs would be very dull. The novelist’s task is both to analyse and to indicate mystery, at the same time. My attitude to the emotional life of my characters is similar to much else in writing: a mixture of subjective involvement and emotional control. My work isn’t, however, autobiographical, except maybe for the first third of my first novel. I don’t believe in the novel as confession, or as therapy – not for me, anyway. Occasionally I might use something from my own life, but if so, it would be in an entirely objective spirit, and almost certainly unidentifiable.

LV. Do you set great store upon a novelist’s sensibility? Between romance and crazy invention of tricks, where do you draw the line?

JB. Well, a novelist’s sensibility is what a novelist is, as distinct from any other novelist; it is the heart-beat and the fingerprint. I think my sensibility involves a fairly wide spectrum of tonalities, as you imply; but I think that is, after all, the modern sensibility (though it is also the Shakespearean sensibility).

LV. You write a kind of dystopia of feelings (an absence that will make the heart grow fonder). Do you agree this may be a desperate warning that the Desperado novel needs new experiences? Do you identify with the idea of dystopic emotions?

JB. I don’t really understand your question. I often write about the darker side of things, true (though not many people get murdered in my fiction – so far). And I agree with

Chekhov’s advice to a fellow-writer, ‘If you want to move (the reader), be colder.’ i.e. be restrained in technique, don’t ever tell the reader what s/he is meant to feel.

LV. Your work as a lexicographer on the Oxford English Dictionary may have influenced your style, which is both confusingly rich in synonyms and subtly witty. For the stream of consciousness the novel concentrated in the style. You have definitely come back to the story, yet your focus is much more complex. How would you describe it?

JB. I don’t think the OED affected my writing. It may have made me a better Scrabble player, but only in the range of words beginning with C,D,E,F or G. But style is central. People who don’t understand style think it is like a coat of gloss paint applied to the story to make it shine. That’s nonsense. Style, form, theme, all pull equally to convey the truth of life.

LV. Writing thrillers brings you to the core of plot before everything else. Do you write them under a pseudonym because your real work is meant to reach farther than the plot, or would you rather skip the question?

JB. Yes, thrillers are more plot-filled, though one of the complaints about my thrillers was that they were all atmosphere, character & menace, and not enough plot. I wrote the four thrillers that I did very quickly, as a relaxation. I don’t disown them, but I’ve never reread them, so don’t really have an opinion. It takes me 2-3 years to write a novel; it used to take me 2-3 weeks to write a thriller. That’s about the relative level of importance I accord them.

LV. Among other statements, you once claimed you have become a writer for ‘love of words’ and ‘distaste for office hours.’ Your credo could be concentrated in these two phrases: tricky manner and totally unorthodox mood. You love words but do not service them. You destroy any timetable of meaning while hiding inside a perfect plot. You want your readers, yet you shame them into silence. Do you enjoy reactions from them? Do you want to know what critics and common readers find in you? Last but definitely more than least, do you welcome/ tolerate/ hate interviews?

JB. Well, that was two out of a number of reasons I gave. I was trying to say that I am temperamentally suited to being a writer (which many writers aren’t) as well as deeply

committed to the novel as an art form. I don’t think I ‘shame my readers into silence’ (it didn’t work with you, did it?). I get quite a few letters from readers. Interviews? I’d say I tolerate them rather than welcome or hate. It depends on the questions, partly. But I do think that the recent mania for artists of all sorts to be obliged to explain themselves as soon as they produce anything is a bit absurd. And not anything they’re necessarily much good at.

LV. You claim that the novel will ‘outlast even God.’ Is its vitality rooted in language, plot or technicalities that can constantly be innovated? Is innovation a reason for or against the survival of the novel?

JB. Yes, my view is that god is probably a novelist’s invention (though I stand to be corrected if he tells me otherwise). Like all art forms, it must innovate to survive. But I think it will survive because of the amount of truth it tells (our species loves to deceive itself, but also hungers for truth), and the fact that other art forms cannot tell those truths in the way the novel does. The cinema is a miraculous rival, which does some things better, but which can never match the novel for the inner line, the emotional life, the reflective life, the private life – or the private, solitary, intense reader’s experience of those things.

LV. Your Flaubert’s Parrot is a masterful illustration of the hybridization of literary genres. You mix fiction, poetry, drama, literary criticism, literary history, even test papers of academic life into it. You build a story within a story, an age inhabits another, characters melt in one, the author himself. Is this author the main character of your novels, a histrionic mind that hides a desperately introvert sensibility? Is the author still in hiding in your novels (as he was in Joyce’s)?

JB. I believe, with Flaubert, that the novelist should be in his work as God is in the universe, everywhere present and nowhere visible. He succeeded in being more invisible than me, probably. I do also take an inclusive view of what the novel is and can be. If my theme requires non-fictional elements, then so be it – though there will always be a fictional, a novelistic shaping to the narrative of those non-fictional elements.

LV. I have called you a ‘Desperado of witty fiction.’ Your message reaches far deeper than that. Where do you think your sense of humour ends (if that ever happens) and yields the stage to something devastatingly earnest? How would you put into words your most hidden feature, the one we have to wonder at from afar unless we can talk to you face to face?

JB. I believe that being funny is a good way of being serious; but being serious is also a good way of being serious. The British literary culture is, after all, not monolithic or as genre-specific as the French equivalent. Compare Shakespeare with Racine. And we all – novelists and playwrights – descend from Shakespeare, where the Fool often speaks wisdom and the Wise Man speaks folly. Or – more truthfully – people are a mixture of both and get things wrong as often as they get things right.

LV. You manage to turn literary criticism into a thriller, in Flaubert’s Parrot. What kind of critics do you approve of? Between deconstruction and various ‘-isms’ (see Eliot’s hatred of ‘Leavisitism’), where do you draw the line? How far can a critic go with your novels and not upset their author?

JB. I approve of critics who are modest, careful, and doubt-filled; who try to do that hardest of things, give an accurate description of the novel and how it works – who feel its pulse, recognize its tonality, understand what isn’t there, and so on. Most critics rush through an inadequate plot-summary in order to get to what really interests them – their Olympian judgment. Judgement should, however, emerge through summary of the book. The great English critic and short-story writer VS Pritchett understood this. Some people, reading his criticism, think he is merely describing what is going on in Turgenev, or Chekhov. In fact, it’s brilliant criticism of literature – and life— at the same time. How far can a critic go with my novels and not upset me? As far as he likes, because nowadays I don’t read criticism of my work. In the past it’s been a support for the ego, never the slightest help in writing the next book. So I’ve given it up. Giving up criticism is much easier than giving up alcohol or tobacco, I can tell you.

LV. Your novel Staring at the Sun is an epic poem, too. In Talking It Over you experiment with fiction submerged in drama. Here you blend prose and poetry. This novel puts the reader in a blessing mood. Your irony rescues the show and charms the plot alive, like Sleeping Beauty. From symbols to dystopia, you run up and down the ladder of emotions. Have you written any poetry at all? Do you consider doing it from now on? Is lyricism important to you as a preeminently witty author of fiction?

JB. I did write poetry a little, from the ages of about 16 or so to about 25. But it wasn’t any good. It was always prosey, argumentative poetry. I think I’m better at writing lyrical prose than prosey poetry.

LV. One last question: how much do you know about the communist reality you described in The Porcupine? What does the fall of communism mean to you?

JB. Well, I was born in 1946, so I’m a child of the Cold war. At school and university I studied Russian. In 1965 I went on a big trip with friends – driving from England through Germany and Poland to Russia, up to Leningrad, down to Kiev and Odessa, into Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and home. I visited Romania again in 1979 – indeed, proposed to my wife in your country. I’ve been to Bulgaria twice, once just before Communism collapsed, once as it did so. So I know something of the background, and when writing The Porcupine I was helped by Bulgarian friends with certain details. I view the fall of Communism as a largely joyous event in itself, though I view much of what followed – the triumphalism of the West, the weakening of the Left’s good, true ideas (as opposed to its totalitarian tendencies), the brutal bullying of the spreading capitalist system – with dismay.

November 8, 2000